Etchings

In addition to his extensive oeuvre of paintings and drawings, Rembrandt van Rijn also produced around 290 prints. His mastery in this field is undisputed; he is generally acknowledged as one of the great etchers- if not the greatest- of all time. Rembrandt acquired a European reputation in his own lifetime precisely because of his graphic work, which, because it could be reproduced, was much more widely known than his paintings or drawings.

The Rembrandt House Museum owns an almost complete collection of Rembrandt’s world-famous etchings.

Rembrandt’s free use of line, the unique deep black of many of his etchings and his masterly use of the drypoint were very popular and his work was much sought after by the many print collectors of the time.

Etching was not a sideline where Rembrandt was concerned. His prints cannot be regarded as inferior by-products of his paintings, which nowadays are much more famous. Rembrandt took his graphic art very seriously for almost the whole of his working life – during the early years as a young artist in Leiden, the town where he was born, and while he was in his prime as a successful master in Amsterdam. It was not until he was approaching the end of his life that he gradually gave up etching.

Landscapes

Landscape prints were immensely popular in the 17th century. The portrayal of the Dutch landscape reached its zenith in Rembrandt’s work. Altogether Rembrandt made 26 landscape prints. They all date from the 1640-1653 period. Rembrandt’s landscapes were usually produced in his studio on the basis of drawings he had made during walks in the countryside around Amsterdam. In some cases he probably worked straight into the copper plate on the spot. Six’s Bridge and the Clump of trees with a vista are examples of this. The rapid and spontaneous drawing lends these prints the feeling of having been made in the open air. The three trees is Rembrandt’s most famous landscape etching. The trees were probably on the Diemerzeedijk. The silhouette of Amsterdam can be seen in the background. In this etching, Rembrandt exploited the effect of strong contrasts between light and shade. The darker passages were accentuated with drypoint and burin. Rembrandt’s early landscape etchings are entirely etched. The foreground of these etchings is always meticulously worked out and placed against a lightly indicated horizon. In his later landscapes Rembrandt combined the etching technique with drypoint and burin. He also sometimes added imaginary elements—such as mountains and exotic buildings—to the typical Dutch landscape.

Rembrandt, The Omval, 1645. Etching and drypoint (state II), 184 x 225 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

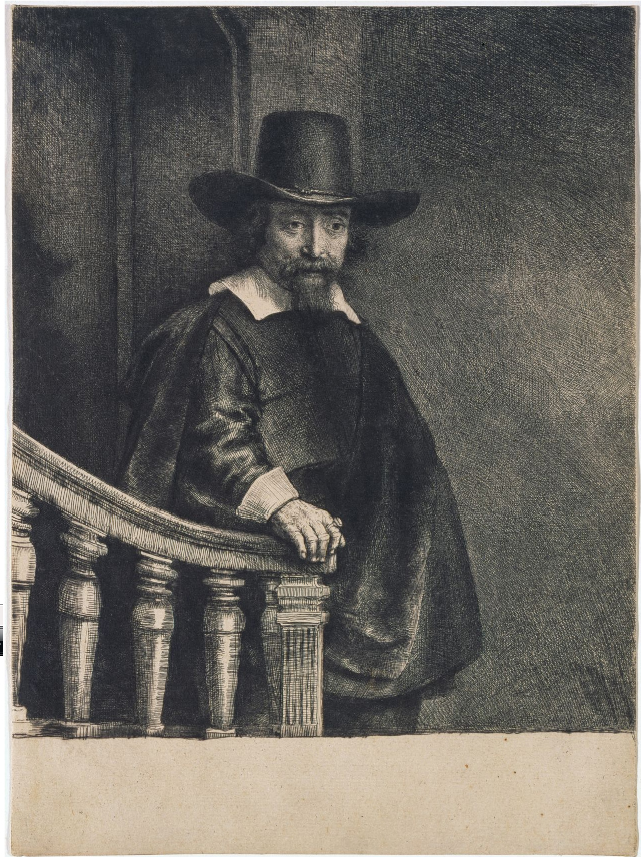

Portraits

Rembrandt etched some twenty portraits between 1633 and 1664. Most of them were commissioned by patrons. As a rule they were intended for use in the sitters’ private circles. In one or two cases we know the reason for the commission. The preacher Jan Cornelis Sylvius, for instance, had his portrait etched by Rembrandt when he left Amsterdam. The prints were intended as mementoes for his friends in Amsterdam. When he died sixteen years later, the plate was printed again. Many of the subjects of these portraits were acquaintances or even friends of Rembrandt’s. Clement de Jonghe was a print dealer. He owned a great many of Rembrandt’s etching plates. The apothecary Abraham Francen was guardian to Rembrandt’s daughter Cornelia. One of Rembrandt’s most admired portraits is that of his friend Jan Six. Rembrandt drew three preliminary studies for this carefully executed print. Two studies, and the etching plate, are still owned by the Six family. Rembrandt’s earliest portraits are simple in structure and technical execution. Later portraits are remarkable for their complex composition and elaborate detailing. Rembrandt was able to achieve painterly effects by combining the etching technique with the use of the drypoint and burin.

Rembrandt, Ephraim Bueno, 1647. Etching, drypoint and burin (state II), 241 x 177 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

Self-portraits

Rembrandt made an extraordinary series of 32 self-portrait etchings. Most of them were produced in the period 1628-1630, when Rembrandt was still living in Leiden. These prints are very small. Most of them show only the head, although in some cases part of the upper body can be seen. In these early self-portraits Rembrandt was practising portraying facial expressions. He pulled all sorts of faces in front of a mirror and recorded what he saw on an etching plate. By doing this, he taught himself to show moods and emotions. He also used these etchings to study the way the light fell on his face. He used what he learned for the figures in larger compositions. Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam in 1631. By this time he was already a famous artist. His success is reflected in his self-portraits. In 1639 he made a portrait of himself as a nobleman, looking out self-confidently at the viewer. The pose is borrowed from Titian’s famous portrait of Ariosto. For other self-portraits he decked himself out in expensive costumes with exotic accessories, of which he owned a great many. After 1640 Rembrandt’s portraits become more sober. His last etched self-portrait dates from 1648, when he was 42.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with curly hair, c. 1629. Etching (state II), 56 x 49 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

Faces

Early in his career Rembrandt etched more than thirty studies of men and women. They were not meant to be portraits—they were a way for Rembrandt to practise capturing facial expressions. These heads of striking types are known as ‘tronies’. Most of the tronies were made between 1630 and 1640. Rembrandt’s parents often acted as his models. With their wrinkled and lived-in faces they made superb subjects. Four Oriental heads of 1635 make up a separate group in this category. They are based on prints by Jan Lievens. Rembrandt wanted to improve on his rival’s work, as the inscription on this print reveals.

Rembrandt, Sheet of studies: self-portrait, a beggar couple, heads of an old man and old woman, etc., c. 1632. Etching (state II), 100 x 105 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum

Nudes

Apprentice artists started their training by copying drawings and etchings. They then moved on to drawing plaster models. It was only later that they began drawing nude models. The pupils in Rembrandt’s studio drew and etched from life. There are fourteen prints of this kind by Rembrandt. In the 1640s Rembrandt etched a number of male nudes. They were probably all drawn directly into the etching plates. The drawing manner is always loose and open, and the models are positioned in typical studio poses. One of these etchings includes a child learning to walk in a walking frame. Rembrandt was saying that drawing is like walking—the only way to achieve results is by constant practice. His series of female nudes was made around 1660. In contrast to his approach to the male nudes, Rembrandt now concentrated entirely on the play of light and shade. The sharp outlines that he used in his earlier figures have disappeared. Rembrandt often depicted his models with great realism. In so doing, he was flying in the face of the art orthodoxy of the time. Many of his contemporaries were not impressed. The subjects of some nude studies are derived from classical mythology. Nevertheless these prints are primarily intended as studies of the female nude.

Rembrandt, Nude Woman Seated on a Mound, c. 1631. Etching (state III), 177 x 160 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

Biblical scenes

The Bible was Rembrandt’s most important source of inspiration. He devoted more than eighty prints to biblical subjects. Some Bible stories appealed to him to such an extent that he depicted them more than once—for instance the events in the lives of Abraham, Tobias and Christ. The Old Testament is the first part of the Bible. It contains stories about the creation and the earliest history of the Jewish people. The lives of the patriarchs, Abraham, Jacob and Joseph, particularly appealed to Rembrandt. He almost always chose a moment full of tension and drama. Abraham’s sacrifice shows the angel staying Abraham’s hand and stopping him from sacrificing Isaac at the last moment. Christ’s life and passion are described in the New Testament, the second part of the Bible. Rembrandt’s most important prints are based on New Testament stories. But he did not always take the Bible as his source. He also used prints or paintings by illustrious predecessors. For The Triumph of Mordecai Rembrandt quoted from a painting by his teacher, Pieter Lastman, borrowing the composition, the building in the background and the poses of the main characters. As well as Bible stories, Rembrandt also chose saints as subjects for his prints. He had a particular liking for St Jerome, and devoted no fewer than seven prints to this learned hermit.

Rembrandt, Christ preaching (‘The hundred-guilder print’), c. 1643-49. Etching, drypoint and burin, Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

Genre

Rembrandt used scenes from everyday life in more than fifty of his etchings. They reflect his lively interest in depicting street characters like tramps, quacks and strolling musicians. Works like this are traditionally described as ‘genre’ scenes. While they appear to be of everyday subjects, genre scenes often make a moral point. In Rembrandt’s case, however, there generally does not seem to be any message of this kind. Rembrandt etched a great many genre scenes, particularly at the start of his career. These prints are usually small. A scene often contains only a single figure. In a few cases he worked out a street scene in detail. The rat-poison pedlar is an example. It was one of Rembrandt’s most popular prints in the 17th century. Unlike his contemporaries, Rembrandt depicted the street figures with great humanity. Some scenes take place in the dark of night. Night scenes were a speciality of the Dutch graphic artists. Rembrandt excelled in them.

Rembrandt, The rat-poison pedlar (‘The Rat catcher’), 1632. Etching (state III), 140 x 125 mm., Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum.

Rembrandt’s etching plates

The etching plates by Rembrandt that still survive have passed through numerous hands over the centuries. A large number of them came into the possession of the Amsterdam publisher and printseller Clement de Jonghe (1624-77). No fewer than 74 plates are listed in his estate.

Many of these etching plates turn up in the 18th century in the estate of the Amsterdam merchant and collector Pieter de Haan (1723-66). After his death they were sold. Most of them went to engraver and Rembrandt connoisseur Claude-Henri Watelet (1718-86) in Paris.

Watelet reworked some of the plates with an etching or engraving technique in order to make new impressions from them. This happened much more often thereafter and people were not always very careful about it. They often added lines and sometimes even changed the composition.

After Watelet the plates were reworked and reprinted by their next owner, the printseller and publisher Pierre-François Basan (1723-97). In the 19th century they became the property of the French publisher Auguste Jean and after him of the engraver Auguste Bernard, both of whom brought out new impressions.

In 1906 the Paris collector Alvin-Beaumont bought the plates from Auguste Bernard’s son. To mark the tercentenary of Rembrandt’s birth Alvin-Beaumont made a small number of impressions of each plate, which he presented to various dignitaries and museums. Shortly after 1916 the plates were inked and lacquered in order to make further printing impossible.

After abortive negotiations with the Rijksmuseum and the British Museum, Alvin-Beaumont finally sold the etching plates in 1938 to the American collector Robert Lee Humber. He placed them on loan in the Raleigh Art Museum in North Carolina.

In 1993 the heirs of Lee Humber, who had died in the meantime, put the etching plates on the art market. The assemblage that had remained intact up to then was broken up, passing into the hands of museums, dealers and private individuals all over the world.

The Rembrandt House, the Rijksmuseum and the Amsterdams Historisch Museum have acquired some fine examples from this inheritance. Thus after over two hundred years some of Rembrandt’s etching plates have finally returned to the Netherlands. Their acquisition was made possible by the aid of the Rembrandt Society, the Ministry of Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs, the VSB Fund and the Society of Friends of the Rembrandt House.