Cleaned

Ferdinand Bol, Elisha Refusing the Gifts of Naaman, 1661. Oil on canvas, 151 x 249 cm. Long term loan, Amsterdam Museum. Photo after conservation. Photographer: Monique Vermeulen, Amsterdam Museum

Cleaned!

This painting has now been conserved, and we can once again see it in all its glory. This is good news, as it is an important work of art for the Rembrandt House Museum, because:

- it was painted by one of Rembrandt’s most successful pupils, Ferdinand Bol.

- it comes from the neighbourhood of the Rembrandt House, where it hung in the Leprozenhuis, at the end of the Jodenbreestraat

- it is an artistic masterpiece with a link to Rembrandt’s teacher Pieter Lastman

You can read more below about this remarkable painting and its conservation. The treatment was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Vereniging Rembrandt (and its BankGiro Loterij Restauratiefonds) and the BROERE CHARITABLE FOUNDATION

Painter to the elite

Ferdinand Bol (Dordrecht 1616-1680 Amsterdam) was one of Rembrandt’s most successful pupils. After his period of study with Rembrandt (between 1636 and 1640) he made waves as painter of portraits as well as Biblical and mythological scenes. At first his work was similar to Rembrandt’s. But from around 1650 onwards he painted in a smoother, more idealized style. This netted him great success with Amsterdam’s elite, of which he in turn became a member. After his second marriage with a wealthy woman, he lived at Keizersgracht 672, presently the Museum Van Loon.

Eastern part of the city of Amsterdam, detail of the map of 1625 by Balthasar Florisz. The orange arrow indicates Rembrandt’s house, the blue arrow the Leprozenhuis.

Leper’s Hospital

Bol made this large painting on commission from the Amsterdam Leper’s Hospital. It hung there in the Chamber of the Regents, the administrators of this charitable institution. The Leprozenhuis stood at the end of the Jodenbreestraat (presently the Mr. Daniël Visserplein). Originally this fell outside the city, because it housed people with leprosy, a very contagious disease. With the expansion of the city in the 17th century it came to lie just inside the city’s border. Because leprosy was better controlled by then, other patients were also admitted.

An exemplary scene

The painting represents a story from the Bible that correspondingly concerns leprosy. To the right of centre stand Naaman and Elisha. Naaman was a military hero from Syria who enjoyed great success on the battlefield but who was afflicted with leprosy. On the recommendation of a Jewish servant he travelled to Israel, to the prophet Elisha. He was instructed to submerge himself seven times in the River Jordan. And indeed, he recovered. To thank Elisha Naaman returned with many gifts. This moment is shown here. Naaman wants to reward Elisha for his help but Elisha refuses, saying “As long as the Lord whom I serve lives, I will accept nothing”. The message is clear: just like Elisha, the regents do their work for the Leper’s Hospital out of charity. Not to enrich themselves.

An additional warning

The scene incorporates an additional warning, for those who nonetheless threatened to succumb to the temptation of money. In the doorway to the right we see Elisha’s servant Gehazi. He listens to the conversation between Elisha and Gehazi. After Naaman’s departure he catches up to the Syrian company in order to secure some gifts for himself. On his return Elisha has surmised Gehazi’s deed and punishes him, with leprosy.

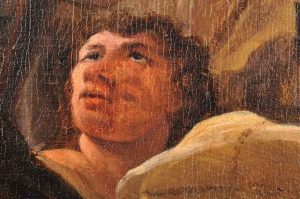

Pieter Lastman, The Crucifixion of Christ on Golgotha, 1616. Oil on canvas (transferred to panel), 90 x 137 cm. Amsterdam, The Rembrandt House Museum

Inspiration from the teacher of the teacher

Bol took inspiration for this painting from Rembrandt’s teacher Pieter Lastman (1583-1633). This is especially evident to the left in the painting. Bol stacked up his figures in order to suggest a large group standing there. This is a trick that Lastman often used, as seen in various paintings by him in the Entrance Hall of the Rembrandt House. We also see the camel and the parasol more often in his work. Lastman had been dead for thirty years when Bol made this painting, but his work was evidently not at all forgotten.

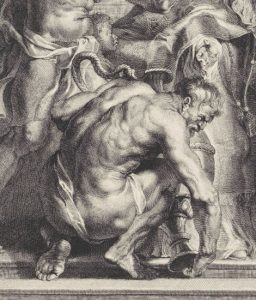

(detail of) Hans Witdoeck, after Peter Paul Rubens, Abraham and Melchizedek, 1638. Engraving, 405 x 459 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Other artistic models

Bol drew on other models as well for this painting. The crouching man in the centre who puts down a vase was taken from a print after a painting by Peter Paul Rubens. And for the figure of a donkey Bol looked to an etching by Karel Dujardin.

The need for conservation

This painting was treated in the first half of 2021 by conservators Herman van Putten and Mireille Engel. The last time this work underwent thorough treatment was in 1945. In the meantime the canvas had begun to develop cracks in several places, with the paint curling up at the edges of the cracks. In other places it formed raised flakes. In order to prevent the paint from coming loose, they had to be flattened and re-adhered. Besides this, the varnish layer had discoloured and old retouching had changed in colour. These had to be removed and replaced. With the cleaning of the dirty varnish and the old retouches the painting has regained its vibrant palette and details are now much more legible. Also striking is the sky, its pink and orange hues lending the scene a warm glow.

The dog with two heads. Bol moved the head from the higher to the lower position. Photographer: Herman van Putten

Re-emerging eye and eyebrow visible through the paint in the group to the left. This figure was initially farther down in the composition. Photographer: Herman van Putten

Visible changes

All kinds of changes that Bol made while painting (pentimenti) became visible when the painting was freed of the dirty varnish and old overpainting. In some places the overlying paint layer had become thinner and more translucent, and the underlying paint layers became more visible. The most striking of these pentimenti are the reduction in size of the dog between the two main figures, the displacement of Elisha’s hand, the shortening of Naaman’s robe and the move of the face of a figure in the group to the left. These were photographed and documented by the conservators, and subsequently subtly toned down (retouched).

Source: http://www.mokums.nl

|

Source: www.onderdekeizerskroon.nl

|

In its place in the Rembrandt House

The cleaned painting can be seen in the Salon (Sael) of the Rembrandt House. A wonderful spot, where the painting’s various stories come to life almost on their own. Part of the Leprozenhuis, which was demolished in 1860, can be seen nearby. The Lazaruspoort that offered access to the building was moved in 1976 and since that time stands diagonally across from the Rembrandt House, on the Sint Antoniesluis. Upon leaving the museum in the direction of the Nieuwmarkt, you can walk by it.